The removal of Shen Yun from Montreal’s Place des Arts isn’t censorship, it’s accountability. Here’s why more cities should follow suit.

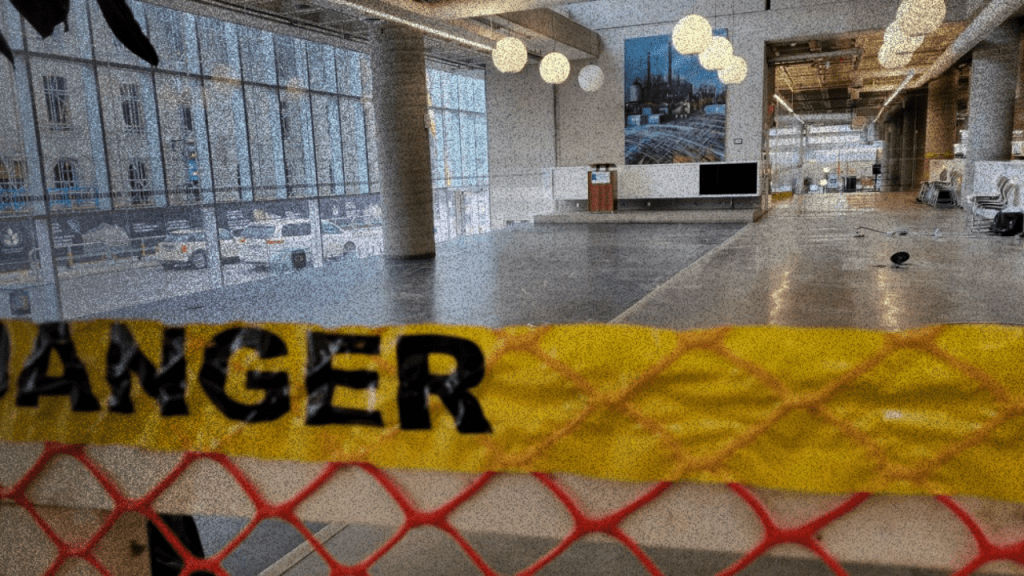

When Montreal’s Place des Arts announced that Shen Yun would be removed from its 2026 lineup, it sparked a flurry of confusion and controversy.

For many, Shen Yun is nothing more than an elegant cultural showcase: sweeping dance routines, dazzling costumes, and traditional Chinese music.

But the cancellation pulled back the curtain on what the show really represents. This wasn’t just a logistical decision or a matter of scheduling; it was a response to growing awareness about how art can be weaponized to manipulate, misinform, and divide.

What Is Shen Yun, Really?

Shen Yun is a touring performance group based in the United States, run by adherents of Falun Gong—a spiritual movement banned in China.

While it brands itself as a revival of 5,000 years of Chinese civilization, the show is in fact a polished vehicle for anti-communist propaganda, anti-scientific conspiracies, and extremist ideology.

The performances often include veiled (and sometimes not-so-veiled) messages denouncing atheism, Darwinian evolution, feminism, LGBTQ+ rights, and the Chinese Communist Party.

Audiences, often unaware of this underlying agenda, are lured in by the promise of cultural spectacle. But what they receive is a jarring juxtaposition of classical aesthetics and political dogma.

Interludes between dances feature narration warning about impending spiritual warfare or the collapse of civilization. It’s not art for art’s sake; it’s a well-funded attempt to launder ideology through heritage.

Why Shen Yun Is Problematic

The problem with Shen Yun isn’t simply that it expresses a political point of view—many artists do. The issue is that it hides that agenda behind a smokescreen of culture and beauty, misleading audiences into thinking they’re attending a celebration of Chinese heritage when they’re actually being exposed to the beliefs of a fringe spiritual-political movement.

That movement is Falun Gong, founded in China in 1992 by Li Hongzhi. While it began as a qigong-based spiritual practice blending breathing exercises, meditation, and moral teachings, Falun Gong quickly evolved into a rigid ideology that claims to offer salvation from a decaying world.

Li’s teachings assert that humanity is under threat from “demons” manifested as modern science, homosexuality, race-mixing, and communism. He claims to possess supernatural abilities and encourages followers to avoid medicine and reject the idea of racial and cultural diversity.

After the Chinese government banned Falun Gong in 1999—citing its cult-like structure and mass mobilization capacity—the group rebranded itself abroad as a persecuted movement, gaining support among Western conservatives and anti-communist groups.

In exile, Falun Gong built a media and propaganda empire to amplify its worldview, most notably through the founding of The Epoch Times.

The newspaper, once obscure, has become one of the most prominent far-right outlets in North America, known for spreading conspiracy theories about COVID-19, QAnon, anti-vaccine disinformation, and aggressive anti-China rhetoric.

Shen Yun is the cultural arm of this broader project. It packages Falun Gong’s worldview in a format palatable to Western audiences—combining stunning visuals and traditional music with subtle (and sometimes overt) ideological cues. Behind the stagecraft, however, is a labor regime that mirrors the group’s authoritarian tendencies.

Former Shen Yun performers have described grueling schedules, cult-like restrictions on personal freedom, and ideological conditioning. Many lived under surveillance, were prohibited from dating or speaking to outsiders, and worked for little or no pay.

Similarly, journalists and staff at The Epoch Times have reported being pushed to work long hours for low compensation, often under strict editorial and ideological control.

For both Shen Yun and The Epoch Times, dissent or deviation from Falun Gong’s teachings can result in shunning or expulsion from the community.

Though not formally classified as slave labor, these accounts paint a picture of exploitative, highly controlled environments where labor is extracted under intense ideological and social pressure.

For international audiences unaware of this internal reality, the cultural packaging obscures the human cost behind the performance.

The impact is real: Shen Yun fosters misunderstanding of modern China, fuels anti-Asian sentiment masked as concern for human rights, and reinforces Cold War-style binaries of good vs. evil, East vs. West.

Montreal as a Turning Point

Montreal’s decision to cancel Shen Yun was not made in a vacuum. The public is becoming more informed, and voices critical of Shen Yun’s real message have grown louder.

Online discussions, firsthand accounts, and investigative reports have all contributed to a clearer picture of what Shen Yun represents. Place des Arts cited the performers’ affiliation with Falun Gong and the controversial political content as core reasons for pulling the show.

This marks a shift. For years, institutions have hosted Shen Yun unquestioningly, falling for its branding as “authentic Chinese culture.” But Montreal is now setting a precedent: that public cultural venues—especially ones funded by taxpayers—have a duty to be transparent about what they host and why.

Montreal Isn’t Alone

Montreal’s move fits into a broader international pattern. In South Korea, multiple performances were pulled after pressure from the Chinese Embassy, prompting legal battles over censorship and sovereignty.

Over the years, venues across Europe—including in Ireland, Germany, and Spain—have faced cancellations, diplomatic pressure, or protests related to hosting Shen Yun. While this pattern isn’t new, it appears to be intensifying as anti-China and anti-communist narratives gain traction in many institutional spaces.

In that climate, Montreal’s decision stands out. It reflects a growing recognition that Shen Yun is not just a dance show, but a vehicle for geopolitical messaging wrapped in aesthetics. The wave of cancellations worldwide suggests a broader shift: institutions are beginning to question whether they’re platforming culture—or propaganda.

Why More People Need to Speak Out

What happened in Montreal should be a model for other cities. The more people understand that Shen Yun is not a neutral cultural event but a coordinated soft power strategy, the easier it becomes to hold venues accountable for platforming it.

Communities have the right to ask: Who is funding this? What are they really saying? And why is it being presented as apolitical art?

This isn’t about silencing dissent or banning beliefs—it’s about demanding honesty. Cultural institutions must be spaces of genuine expression and education, not tools for ideological warfare dressed in silk robes.

That demand becomes even more urgent in a climate where anti-Asian racism is rising.

A 2022 report by Project 1907 and the Chinese Canadian National Council recorded a 47% spike in anti-Asian incidents across Canada, fueled in part by Cold War–style narratives and COVID-era scapegoating.

In that context, platforming manipulative content masquerading as culture only adds fuel to the fire.

As more people become aware, public pressure can ensure that shows like Shen Yun are seen for what they are: not culture, but calculated messaging with political intent.

Beyond the Stage

The Montreal cancellation should not be dismissed as a one-off controversy. It’s part of a broader reckoning with how propaganda can hide in plain sight—especially when cloaked in the aesthetics of tradition. Shen Yun has relied on that disguise for years, but the veil is lifting.

Audiences deserve to know what they’re being sold. Institutions have a responsibility to uphold truth and transparency. And communities everywhere have the power to say: not on our stage.

If you’ve experienced or witnessed anti-Asian racism in Canada, you can report it at Project1907.org, a community-based tool that tracks incidents nationwide in collaboration with the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter (CCNCTO) and Elimin8hate.

Organizations like CAAARC, the Chinese Canadian National Council, and mychinatownmtl also offer support, advocacy, and resources to those affected by anti-Asian racism and to the broader community.