Canada sells itself as a human rights champion, but its role in global policing and migration reveals a deeper complicity in authoritarian systems.

Canada often markets itself as a beacon of global justice—a calm, liberal counterweight to American militarism or European colonial hangovers.

But recent developments in global policing and human rights suggest otherwise. From Afghanistan to Kenya to South Sudan, Canada’s policies and partnerships reveal a nation deeply embedded in the global machinery of authoritarianism.

Whether through its silent backing of punitive refugee policies, its export of crowd-control policing models, or its selective calls for accountability abroad, Canada reveals its complicity in the very abuses it claims to oppose.

Three recent stories—the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) arrest warrants for Taliban leaders, Kenya’s bloody crackdown on anti-government protesters, and the U.S. deportation of migrants to South Sudan—expose the cracks in Canada’s humanitarian image.

In each case, Canada plays a supporting role in structures of repression while distancing itself from the consequences. These are not isolated contradictions. They are features of a larger imperial alignment.

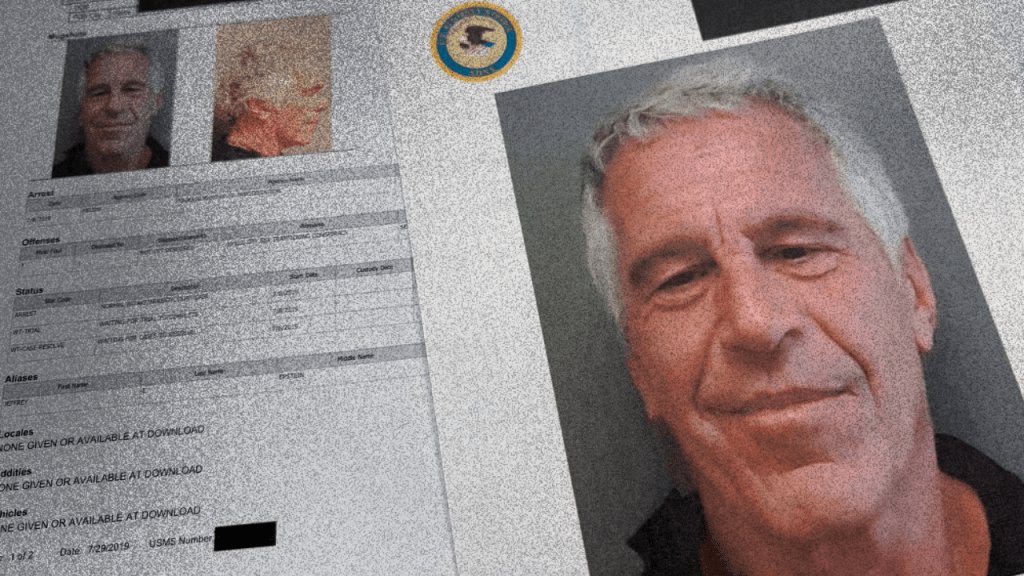

ICC Warrants and Canada’s Afghan Legacy

On July 8, 2025, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for two top Taliban leaders: Supreme Leader Haibatullah Akhundzada and Chief Justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani. The charges—crimes against humanity, specifically the systemic persecution of women, girls, and gender non-conforming people—were welcomed by human rights groups across the globe. Canada, too, voiced strong support for the ICC’s decision, calling it a necessary step toward justice and accountability.

But this is where Canada’s role gets murky. While the Liberal government praised the move, it made no mention of its own legacy in Afghanistan. From 2001 onward, Canada was a major player in the NATO occupation, responsible for training Afghan police forces and contributing to the military apparatus that ultimately collapsed into Taliban control.

These institutions—built with Canadian tax dollars and diplomatic capital—are the very ones now implicated in ongoing violence and gendered repression.

In supporting the ICC, Canada positions itself as a neutral arbiter of justice. But the truth is more uncomfortable: Canada helped build the system that failed—and is now celebrating its punishment from the sidelines.

Kenya’s Protests and Canada’s Exported Repression

From June 9 to July 7, 2025, Kenya was rocked by some of the largest anti-government demonstrations in recent history. Sparked by economic hardship and a deepening cost-of-living crisis, the protests were met with brutal force.

At least 50 people were killed and more than 500 arrested, with reports of extrajudicial killings, abductions, and beatings. On July 7—Saba Saba Day, a symbolic moment for pro-democracy movements, police opened fire on crowds, killing at least 11 in a single day. Some counts later raised the toll to 31.

Kenya’s security forces operate under a familiar structure: underfunded, militarized, and steeped in colonial tradition. Policing there has long been a tool of elite preservation, not public safety. But there’s another player in this system—Canada.

Through development aid, NGO programs, and international training initiatives, Canada has exported its own models of crowd control, surveillance, and “rule-of-law” reform to Kenya for years.

These exports are rarely questioned. Wrapped in the language of human rights and good governance, they often enable precisely the kinds of state violence that erupted last month.

The idea that liberal democracies like Canada are exporting repression under the guise of reform is not just irony—it’s empire. A quieter, more technocratic empire, but an empire nonetheless.

Deportations to South Sudan and Canada’s Refugee Hypocrisy

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the U.S. has begun deporting migrants—including individuals with no connection to South Sudan—to one of the most unstable countries on Earth. In early July, the U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for these deportations, rejecting humanitarian appeals and exposing migrants to state violence, civil war, and forced conscription.

Canada has no direct hand in these deportations. But its own border policy mirrors the same cruelty. Under the Canada–U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA), asylum seekers who arrive via the U.S. are automatically turned away at Canadian border crossings. Canada assumes the U.S. is a safe place for refugees—even when it’s sending them to death.

The contradiction couldn’t be clearer. While Canada celebrates its refugee sponsorship programs and issues statements condemning global displacement, it quietly offloads responsibility onto a partner whose own policies violate international norms. It’s a form of plausible deniability. Canada doesn’t deport to South Sudan—but it knowingly hands asylum seekers to a country that does.

Reckoning with the System, Not Just the Stories

These three stories—Afghanistan, Kenya, South Sudan—are more than headlines. They are case studies in how Canada participates in the global policing of the marginalized, all while maintaining a façade of human rights leadership. Whether by aligning with selective international justice, reinforcing violent police structures abroad, or enabling a system that sends migrants into harm’s way, Canada’s actions speak louder than its diplomacy.

In each case, the pattern is the same: support for global justice in theory, complicity in authoritarian structures in practice. Until Canada reckons with its own role in these systems—at home and abroad—its gestures of solidarity will remain symbolic at best, and hypocritical at worst.

If we want justice, we have to start by naming the real shape of the system—and Canada’s place in it.