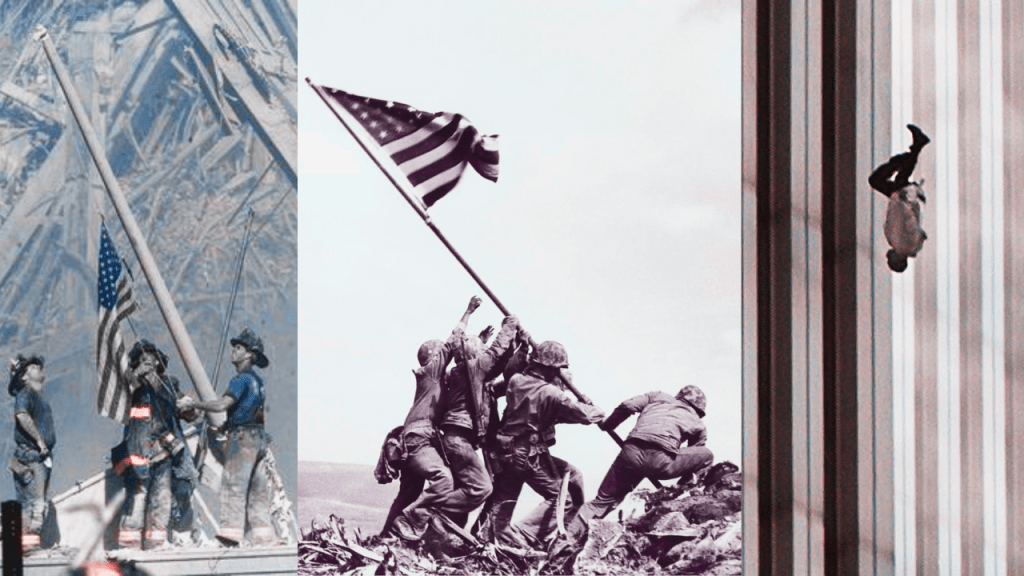

The 9/11 Falling Man photo remains one of the most haunting images of the attacks, sparking debates over its authenticity, media framing, and symbolism.

In the wake of major historical events, certain images emerge as powerful symbols, shaping public perception and collective memory.

However, the authenticity of some of these iconic photographs has recently come under scrutiny, sparking debates about their origins and the intentions behind them.

The Iwo Jima Flag-Raising Photograph

On February 23, 1945, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured an image of six U.S. Marines raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima. Marketed as a spontaneous act of heroism, the image quickly became an enduring symbol of American military triumph and resilience. However, the truth behind this photograph is far less noble.

The widely celebrated image was not the first flag raised that day—an earlier, less dramatic flag had been hoisted before being replaced with the larger, more media-friendly version captured in Rosenthal’s shot. This deliberate decision to stage a more photogenic moment calls into question the integrity of the scene and highlights the careful media orchestration behind war imagery.

Rosenthal’s image was embraced by the U.S. government and used to fuel wartime propaganda efforts, reinforcing a sanitized and glorified depiction of the battle. It also helped justify further bloodshed by framing the brutal conflict as an act of valor rather than a calculated strategic maneuver with high human costs.

While defenders of the photograph argue that it was not technically “staged,” the intentional replacement of the original flag with a larger, more dramatic one undermines its credibility as a spontaneous act of battlefield heroism.

Furthermore, the famous “gung-ho” photograph taken by Rosenthal after the flag-raising, in which the soldiers posed triumphantly, only adds to the artificiality of the entire event.

War photography is often manipulated to serve nationalistic purposes, and the Iwo Jima flag-raising is a prime example of how images can be curated to shape public sentiment rather than document raw reality.

The 9/11 Firefighters Flag-Raising Photograph

Similarly, in the immediate aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks, a poignant photograph emerged of three firefighters raising the American flag amidst the rubble of the World Trade Center. This image drew immediate parallels to Rosenthal’s Iwo Jima photograph, symbolizing resilience and unity in the face of tragedy.

However, just like the flag-raising at Iwo Jima, the scene was captured from multiple angles by different photographers, raising questions about the nature of the moment itself.

The most famous version of this event was taken by Thomas E. Franklin of The Record, but other photographers, including Lori Grinker and Ricky Flores, also documented the flag-raising from different vantage points.

Grinker, a photographer from Contact Press Images, photographed the entire sequence, while Flores, working for The Journal News, managed to position himself inside a nearby building to capture the same moment from an elevated perspective. The fact that multiple professional photographers managed to capture this carefully framed, almost cinematic moment amidst the overwhelming chaos of Ground Zero raises questions about whether this scene was more orchestrated than the public was led to believe.

While defenders of the image argue that the firefighters were simply engaging in an organic patriotic act, the deliberate framing of this moment, and its immediate symbolic alignment with the Iwo Jima flag-raising, suggests a broader media construction of heroism in the midst of tragedy.

Unlike the thousands of other moments of destruction that unfolded that day, this particular image—neatly paralleling a World War II propaganda photograph—was the one that was widely disseminated and immortalized.

This repetition of imagery should make us question why certain moments in history get framed in a way that resonates with public emotion, while others are ignored. If multiple professionals were able to capture these scenes from different angles, in different moments, was it truly spontaneous? Or was this another example of how powerful imagery is curated, chosen, and distributed in a way that aligns with existing national myths?

The “Tourist Guy” Hoax

The ease with which an obviously manipulated image was widely accepted as real speaks to the emotional vulnerability and trauma associated with the 9/11 attacks.

The “Tourist Guy” photograph, which showed a man standing on top of the World Trade Center with a plane approaching behind him, spread rapidly across the internet in the days following the attacks.

Despite its clear absurdity, many accepted the image as real simply because the emotional weight of the event made people less likely to scrutinize what they were seeing.

Eventually, it was revealed that the image was a hoax. The individual in the photo, Hungarian Péter Guzli, had taken the original picture in 1997 and later edited in the plane as a joke for friends. He never intended for the image to spread beyond his personal circle, yet the viral nature of the internet and the heightened emotional state of the public allowed it to take on a life of its own.

What is most concerning about this case is not just that the image was fake, but that it was so easily believed in the first place. The trauma of 9/11 created a psychological environment where emotionally charged visuals, regardless of their authenticity, could be immediately accepted as truth.

This willingness to embrace compelling but fabricated images raises serious concerns about how we process visual information, especially in times of crisis. If a blatantly doctored image like the “Tourist Guy” photo could fool so many, what does that say about the unquestioning acceptance of other, more professionally crafted images associated with 9/11?

This case is a clear example of how deeply trauma influences perception, allowing false imagery to spread unchecked and become part of the collective historical narrative.

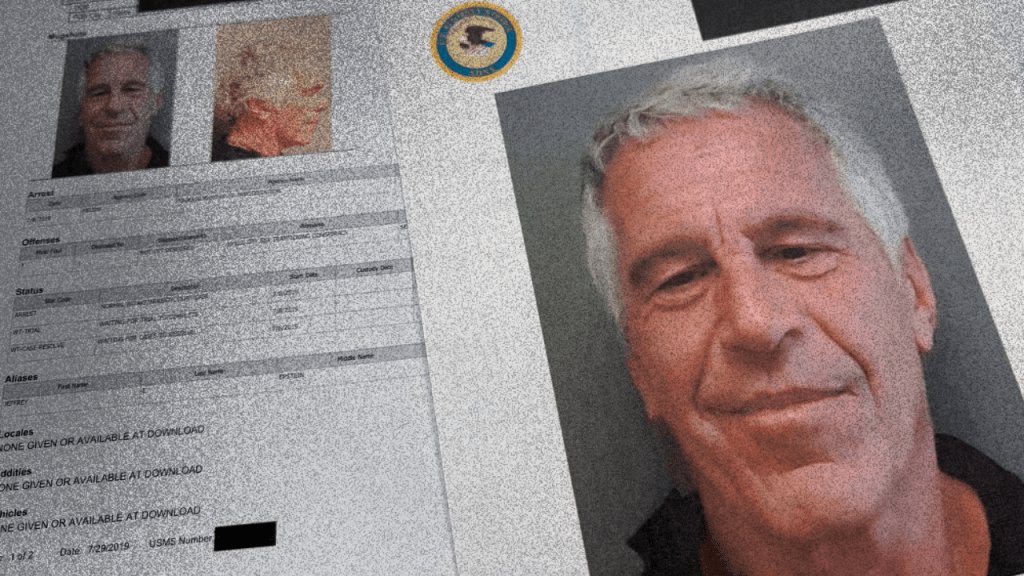

The Role of Photojournalists in Shaping Cultural Narratives

Photojournalists play a pivotal role in capturing moments that define public perception. The recurrence of certain photographers at significant events has led to discussions about the influence and intentions behind these images.

One such example is Doug Mills, a veteran photojournalist for The New York Times, who has been present for multiple defining moments in modern American history.

Mills was among the photographers documenting President George W. Bush on the morning of 9/11, capturing key moments including Bush’s response after learning of the attacks. His photograph from that day has become an essential part of the historical record.

Over two decades later, Doug Mills once again found himself at the center of history, capturing the assassination attempt on Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, on July 13, 2024.

His widely published image of the bullet passing near Trump’s head became an instant symbol of the chaotic political climate in the United States in the lead up to the 2024 election.

The fact that the same photographer was present for both 9/11 and the attempted assassination of a former president raises questions about the presence of certain journalists at key historical moments.

While Mills’ skills and experience make him a natural choice for covering major events, the recurrence of certain photographers at these defining moments fuels speculation about how images are selected, disseminated, and framed to shape public sentiment.

This pattern of certain individuals consistently being in place to capture high-profile moments is not a matter of coincidence alone. The incentive structure of the media industry favors those who can deliver the most compelling images, ensuring that photographers with the ability to shape history through their work are repeatedly positioned at the heart of major events.

If the most powerful photographs of 9/11 and the Trump assassination attempt were taken by the same person, we must ask: to what extent are these images crafted for maximum impact, and how much of what we see is curated to fit a narrative rather than purely captured as it unfolded?

The “Falling Man” and Its Problems with Authenticity

Among the most controversial images from 9/11 is Richard Drew’s “Falling Man” photograph.

The image shows a man falling headfirst from the North Tower, appearing eerily composed in freefall.

While the photograph has been hailed as one of the most powerful and disturbing images of the attacks, its authenticity warrants deeper scrutiny.

Richard Drew is no stranger to capturing tragic historical events. He was one of the four press photographers present during the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, documenting yet another defining moment of American history.

His long career covering major events suggests an ability to be in the right place at the right time—or, perhaps, an awareness of which images will resonate most with the public.

One major issue with the “Falling Man” photograph is its near-perfect symmetry. The subject’s body remains remarkably aligned, a highly improbable posture for someone falling from such a height, particularly considering the effects of air resistance and tumbling motion.

While defenders of the image claim it is merely one frame from a sequence of photos, the choice to highlight this one specific frame, where the man’s form appears controlled rather than chaotic, is questionable.

Furthermore, the identity of the “Falling Man” has never been definitively confirmed. Several theories suggest he may have been a worker at Windows on the World, yet no family has come forward with absolute certainty.

This ambiguity creates an air of detachment around the image, making it feel more like a symbol crafted for media consumption rather than a genuine human moment captured spontaneously.

Another issue lies in how the photograph has been presented. Drew has stated that he did not consciously choose this frame but rather captured a sequence of images in rapid succession using a Canon EOS-1N with a 200mm lens.

While this may be technically feasible, it raises the possibility that the final, widely circulated image was selectively framed or even edited to enhance its emotional impact.

Given the history of staged or manipulated images in war photography, such as the Iwo Jima flag-raising and other controversial wartime images, the potential for selective editing cannot be dismissed outright.

It is important to understand that the argument being made here is not that 9/11 didn’t happen, nor that people didn’t jump from the World Trade Center. The argument is that these images are inauthentic, in that they are highly crafted pieces of propaganda, and the unquestioning acceptance of their authenticity shapes public perception in ways that make deeper scrutiny of the official story irrelevant, simply because of the implications at play.

When emotionally charged but heavily curated images are presented as purely authentic, they override rational analysis and critical inquiry. We have seen time and time again how false or manipulated imagery spreads easily in moments of crisis, particularly in events as defining as 9/11.

The question is not whether the traumatic events occurred—they undeniably did—but rather how these images, selectively framed and widely disseminated, serve to reinforce specific narratives rather than authentically document historical reality.

Just as the “Tourist Guy” hoax showed how easily misinformation can spread, questioning the “Falling Man” does not mean dismissing the horrors of 9/11 but rather emphasizing the importance of ensuring that our collective memory is based on truth rather than carefully crafted imagery.