In a display of system failure and police oversight, the question of how did Zehaf-Bibeau’s car avoid being detected undermines the credibility of state surveillance.

On October 22, 2014, Canada’s official narrative of the Parliament Hill attack was marred by glaring security oversights that raise serious questions about police competence and accountability. Michael Zehaf-Bibeau’s assault—beginning with the murder of Corporal Nathan Cirillo at the National War Memorial and culminating in an assault on the Centre Block where Parliament was in session—reveals more than just a lone act of radical violence. It exposes systemic flaws in how law enforcement monitors and reacts to potential threats.

A particularly disturbing detail in the official story is how Zehaf-Bibeau managed to drive into Ottawa without a proper license plate. Instead of a legitimate temporary plate, he used a piece of junk mail taped to his car.

This makes one wonder how a vehicle without valid identification could pass unnoticed through a city where Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) systems are reportedly widespread. In nearly every major Canadian city, from Montreal to Ottawa, police use ALPR technology to scan vehicles and flag discrepancies. The fact that Zehaf-Bibeau’s car evaded detection for almost 24 hours is not only alarming—it is an indictment of the system’s implementation and the complacency of those tasked with public safety.

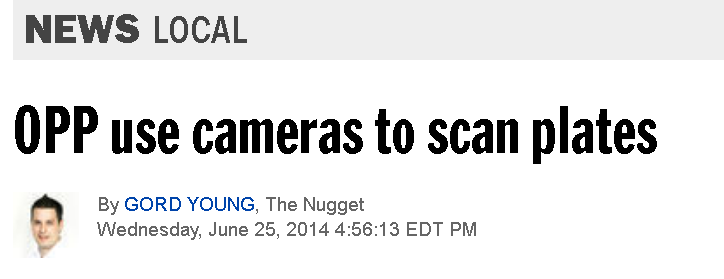

The use of ALPR technology is not a recent innovation. In fact, police and municipal authorities across Ontario have been employing license plate scanning systems since the early 2010s. For example, an article from Nugget.ca in mid-2014 (which has since been deleted) detailed how the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) had been actively using cameras to scan plates, a practice that became integral to investigations such as the high-profile Tim Bosma murder case.

Similarly, the Niagara Falls Review reported in early 2014 (which has also been removed from the website) on the deployment of such systems, highlighting that these cameras could scan approximately 3,000 license plates per hour . Such evidence clearly indicates that the technology was not only available but actively utilized by law enforcement long before the Ottawa shooting.

Despite these capabilities, questions remain about how a vehicle clearly out of compliance with registration laws could circulate undetected. The official narrative has largely downplayed this glaring oversight, suggesting that isolated technical glitches or administrative errors might be to blame. However, such explanations do little to address the broader failure of police to enforce regulations consistently, especially when the public is led to believe that these systems are robust and all-encompassing.

Furthermore, other sources—such as an investigative report on new license plate scanning technology by Blackburn News (which has also been removed from the website) illustrate that municipalities have continuously upgraded these systems to include features that identify expired tags, stolen vehicles, and individuals with prior criminal charges.

Given this context, the fact that Zehaf-Bibeau’s vehicle was allowed to operate so freely for such an extended period points to a disturbing level of complacency and operational failure within Canada’s law enforcement and intelligence communities.

Furthermore, a dashboard camera video appears to show the Ottawa shooting gunman leaving the National War Memorial and entering an illegally parked vehicle on Wellington St. in Ottawa. The car is notably missing a proper rear license plate—an issue that even in the dashcam footage is clearly visible to the human eye.

If such an obvious discrepancy can be detected by an observer, then advanced ALPR technology—designed to capture and analyze license plates in real time—should have easily flagged the inauthentic plate, raising serious questions about the effectiveness of current surveillance practices and police oversight in the nation’s capital.

Ultimately, the Ottawa shooter incident, as officially portrayed, reveals significant gaps that suggest a deeper dynamic at play. The failure to detect a vehicle without a proper license plate—despite the long-established, widespread use of ALPR technology—may not simply reflect technical shortcomings. Instead, it raises the disturbing possibility that such surveillance tools serve as a mechanism in the police’s broader monopoly on violence, reinforcing a system where state power is granted unchecked authority over public safety.