In the aftermath of the Ottawa Attack on Parliament, many still wonder: How did CSIS miss them, and what intelligence failures allowed a threat to unfold?

The attack on Canada’s Parliament Hill earlier this month shocked the nation and prompted intense scrutiny of the country’s intelligence apparatus. The federal government’s response was swift: new legislation, designed to empower security agencies with broader surveillance and enforcement tools, was poised to be introduced almost immediately.

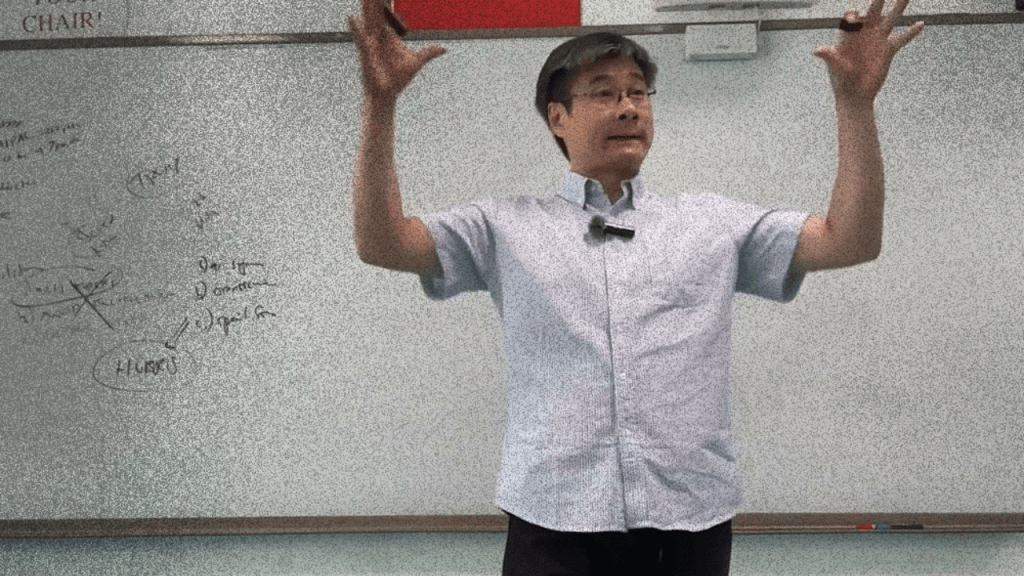

This timing struck Ron Atkey—law professor at Osgoode Hall, former chair of the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC), and an authority on national security law—as supremely ironic.

In a CBC Radio interview with Anna Maria Tremonti, Atkey put it bluntly: “I always think in terms of trying to prevent something before it happens, through good security intelligence.” He went on to question how an individual already on police radar was able to slip through the cracks and carry out a high-profile act of violence on the nation’s capital. “Is our security agency working in cooperation with the police, had information about these individuals—why didn’t they prevent it? How did CSIS miss them?” he asked.

For Atkey, the foundational issue is that preventive intelligence should be the linchpin of any security strategy. “Prevention is always better than after the event,” he emphasized. Yet prevention failed in this case, raising uncomfortable questions about whether the threat was allowed to escalate, or whether systemic flaws—like inter-agency miscommunication—made such a breach possible.

Shortly after the attack, Tremonti mentioned the forthcoming legislation that would grant more robust powers to security agencies. Under normal circumstances, this might be lauded as a timely solution. But Atkey was quick to point out the paradox: “Yes, it’s very ironic; they want to bring in the powers that are necessary. The very acts they are trying to prevent, occur.” The unfortunate scenario, as he framed it, is that the government was poised to legislate exactly the kind of measures that might have thwarted the incident if implemented sooner.

This seeming “perfect storm” of government inaction followed by a swift push for expanded authority has fueled broader skepticism. Critics argue that agencies like the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) may be involved—intentionally or not—in scenarios that either ignore or facilitate potential threats, only to present new powers as a panacea after the fact.

By framing such incidents as proof of the urgent need for greater state control, security agencies and law enforcement can secure political support for expanded surveillance budgets, more aggressive police tactics, and even relaxed oversight mechanisms.

While there is no direct proof that the Ottawa attack was orchestrated or “manufactured,” suspicions arise from cases in other countries where law enforcement has been accused of entrapping individuals—sometimes even providing resources or guidance to push them toward extremist acts.

In those situations, agencies claim success in thwarting plots they themselves partially engineered. Whether the Ottawa incident fits this pattern or is simply an example of failures in information sharing remains an open question.

Yet the timing of the proposed legislation still draws attention to what Atkey called “very ironic” circumstances. From a policy perspective, effective prevention hinges on coordinated intelligence, not merely on new laws. If CSIS and the police already had relevant information, why was it not used properly? Was it, as Atkey wondered, a sign of incompetence, complacency, or something more concerning?

Ultimately, the Parliament Hill attack and its legislative aftermath underscore a delicate balance. Genuine threats do exist, and security agencies need authority to act preemptively. However, the sudden unveiling of legislation—right after a crisis—can suggest an alarming overlap between actual danger and the opportunistic expansion of state power.

As Atkey’s comments remind us, Canada must ensure that in the name of preventing terrorism, it does not grant sweeping new tools without accountability, thereby risking the very freedoms such measures purport to protect.

In the end, the question remains whether the system is simply broken or if there is an intentional effort to manufacture threats to justify expanded powers. Whichever the case, the words of Ron Atkey ring true: “Prevention is always better than after the event.” The challenge for Canadian society is ensuring that prevention does not morph into a pretext for unchecked government authority.